The creation of entirely new materials stands at the heart of scientific innovation and technological progress. From lightweight alloys that enable modern aviation to super-strong polymers in medical devices, materials that did not exist a century ago now shape the world. Understanding how chemists conceptualize, design, and synthesize these substances reveals not only the ingenuity of modern chemistry but also the interplay between theory, experimentation, and societal needs.

The Driving Force Behind New Material Design

The process of designing new materials begins with a question or a problem. Scientists ask: What properties are needed, and how can we achieve them at the molecular level? Unlike merely discovering natural substances, creating a material from scratch requires envisioning structures that meet specific criteria—strength, flexibility, conductivity, thermal stability, or chemical resistance.

This need often arises from societal or technological demands. For instance, the push for more efficient solar panels led to the development of perovskite materials with tailored electronic properties. Similarly, the quest for biocompatible implants drove chemists to design polymers that interact safely with human tissue. By framing the challenge clearly, chemists set the stage for targeted exploration rather than random trial and error.

Understanding Structure-Property Relationships

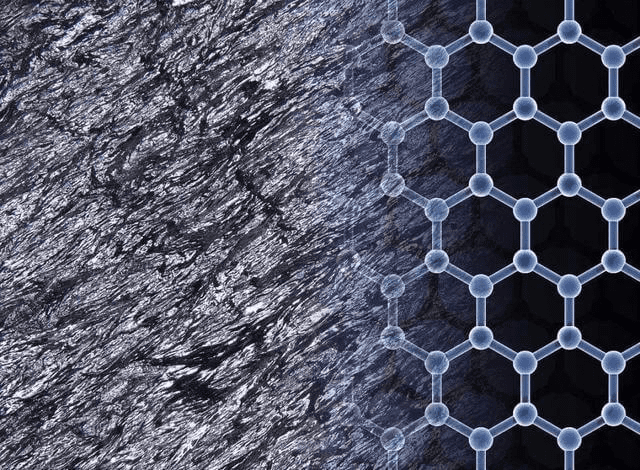

At the heart of material design lies the concept of structure-property relationships. Every property of a material—whether hardness, transparency, or electrical conductivity—stems from its molecular arrangement. Chemists leverage this knowledge to manipulate the building blocks of matter.

For example, carbon is an element that can take several forms: soft graphite, ultra-hard diamond, or the atom-thin sheets of graphene. By controlling how carbon atoms bond, chemists unlock radically different properties. Graphene, with its single layer of atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, is both incredibly strong and highly conductive, demonstrating how subtle changes at the atomic level yield revolutionary materials.

In polymers, the length of chains, degree of branching, and type of monomer determine elasticity, melting point, and chemical resistance. By predicting these outcomes, chemists can design polymers for specific industrial or medical applications before the material is physically synthesized.

Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling

Modern material design heavily relies on computational tools. Before entering the laboratory, chemists simulate how molecules and materials will behave under various conditions. These models can predict stability, reactivity, and mechanical properties, allowing researchers to narrow down promising candidates.

Computational chemistry saves time, reduces cost, and minimizes hazardous experimentation. For instance, in designing catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions, molecular modeling can suggest configurations that maximize efficiency and selectivity. Similarly, predicting the electronic structure of semiconductors enables chemists to design materials for next-generation electronics without synthesizing dozens of unsuccessful prototypes.

These simulations do not replace experimentation—they guide it. The iterative loop of modeling, testing, and refining accelerates innovation and ensures resources are directed toward the most promising avenues.

Synthesis: Turning Ideas into Reality

Once a target structure is identified, chemists move to synthesis, the process of assembling the material. This step often involves balancing theoretical possibilities with practical constraints such as temperature, solvent compatibility, and reaction pathways. A material that looks perfect on paper may prove difficult to produce or unstable in real-world conditions.

Advanced synthesis techniques have expanded the range of materials chemists can create. Methods like sol-gel processing, chemical vapor deposition, and molecular self-assembly allow precise control over the material’s micro- and nanostructure. These techniques are crucial for producing materials with properties unattainable through natural processes, from ultra-porous frameworks used in gas storage to nanostructured metals with unprecedented strength-to-weight ratios.

Synthesis is not merely a technical challenge—it is an experimental art. Chemists must monitor reactions closely, adjust conditions, and sometimes discover unexpected behaviors that reveal new insights. These “happy accidents” can lead to materials with superior or entirely unforeseen properties.

Iteration and Optimization

Designing a new material rarely succeeds on the first attempt. Chemists iterate through cycles of synthesis, testing, and modification. Small adjustments in molecular composition, processing conditions, or structural arrangement can dramatically alter performance.

For example, lithium-ion battery electrodes were refined over decades. Early formulations were functional but inefficient or short-lived. Iterative experimentation—modifying crystal structures, particle sizes, and electrolyte interfaces—yielded today’s high-capacity, long-lasting batteries. This iterative approach reflects a combination of patience, analytical insight, and creativity.

Inspiration from Nature

Nature often provides the blueprint for new materials. Biomimicry involves observing structures in living organisms and translating those principles into synthetic materials. Spider silk, for instance, inspired polymers with exceptional tensile strength, while nacre (mother-of-pearl) influenced layered composites combining toughness and flexibility.

By studying biological materials, chemists uncover strategies honed over millions of years of evolution. These natural templates can be adapted, optimized, or combined with synthetic chemistry to produce materials that did not exist in nature, fulfilling human-engineered requirements.

Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration

Modern material design is rarely confined to a single field. Chemists collaborate with physicists, engineers, biologists, and computational scientists to understand the full spectrum of material behavior. This interdisciplinary approach allows for simultaneous consideration of molecular design, mechanical performance, and application feasibility.

For example, the development of biodegradable plastics required not only polymer chemists but also microbiologists to understand decomposition pathways and environmental scientists to assess ecological impact. Such collaboration ensures that new materials are not only technically impressive but also socially and environmentally responsible.

Testing and Characterization

After synthesis, materials undergo rigorous testing and characterization. Techniques such as X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy, spectroscopy, and mechanical stress analysis reveal structure and performance in detail. These analyses confirm whether the material meets the predicted properties or if further refinement is needed.

Testing is critical because even minor deviations at the nanoscale can impact macroscopic performance. For instance, a tiny defect in a semiconductor crystal can alter conductivity drastically. Detailed characterization ensures that the material is reliable, scalable, and ready for real-world applications.

From Laboratory to Market

The final stage of material design is translating laboratory success into practical use. Scaling production, ensuring cost-effectiveness, and meeting regulatory standards are as important as molecular design. Materials that excel in small-scale tests may fail economically or technically if production is not feasible.

Industry partnerships often play a vital role here. Aerospace, electronics, healthcare, and energy sectors collaborate with chemists to adapt novel materials for specific applications. This collaboration ensures that the potential of a new material is fully realized, impacting products and technologies that reach everyday life.

Ethical and Environmental Considerations

Designing new materials carries responsibility. Chemists must consider the environmental footprint, recyclability, toxicity, and long-term impact of the materials they create. The era of unregulated plastic production demonstrates the consequences of ignoring these factors.

Sustainable material design emphasizes green chemistry principles: minimizing waste, using renewable feedstocks, and reducing energy consumption. Ethical considerations also extend to societal impacts—for example, ensuring materials for medical applications are safe and accessible.

Key Takeaways

- Designing new materials begins with clearly defining desired properties and objectives.

- Structure-property relationships guide chemists in predicting how molecular arrangements determine performance.

- Computational modeling allows rapid exploration of possibilities before physical synthesis.

- Synthesis requires balancing theoretical design with practical chemical realities.

- Iteration and refinement are central to optimizing material properties.

- Nature provides inspiration through biomimicry, offering strategies for innovative design.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration expands the scope and applicability of new materials.

- Rigorous testing ensures reliability, scalability, and alignment with societal and environmental standards.

Conclusion

The creation of materials that never existed before is a testament to human ingenuity and the scientific method. By combining deep understanding of molecular structure, computational prediction, experimental synthesis, and cross-disciplinary collaboration, chemists turn abstract ideas into tangible innovations. These materials not only advance technology but also shape the way we live, bridging imagination and reality in the ongoing quest to understand and improve our world.